Trioceros jacksonii (Jackson's Chameleon) Natural History

The name “Jackson’s Chameleon” covers a diverse group of three horned chameleons. At this time there are three recognized sub-species, but there is no doubt that these three sub-species will eventually be further broken up and some members may even be granted full species status. There is much work to be done to sort out the taxonomy of this chameleon. Presently, the subspecies consist of the following:

Trioceros jacksonii xantholophus (Yellow-crested Jackson’s Chameleon)

Trioceros jacksonii jacksonii (Machakos Hills Jackson’s Chameleon, “True” Jackson’s Chameleon, Rainbow Jackson’s Chameleon, etc…)

Trioceros jacksonii merumontanus (Mt. Meru Jackson’s Chameleon, Dwarf Jackson’s Chameleon)

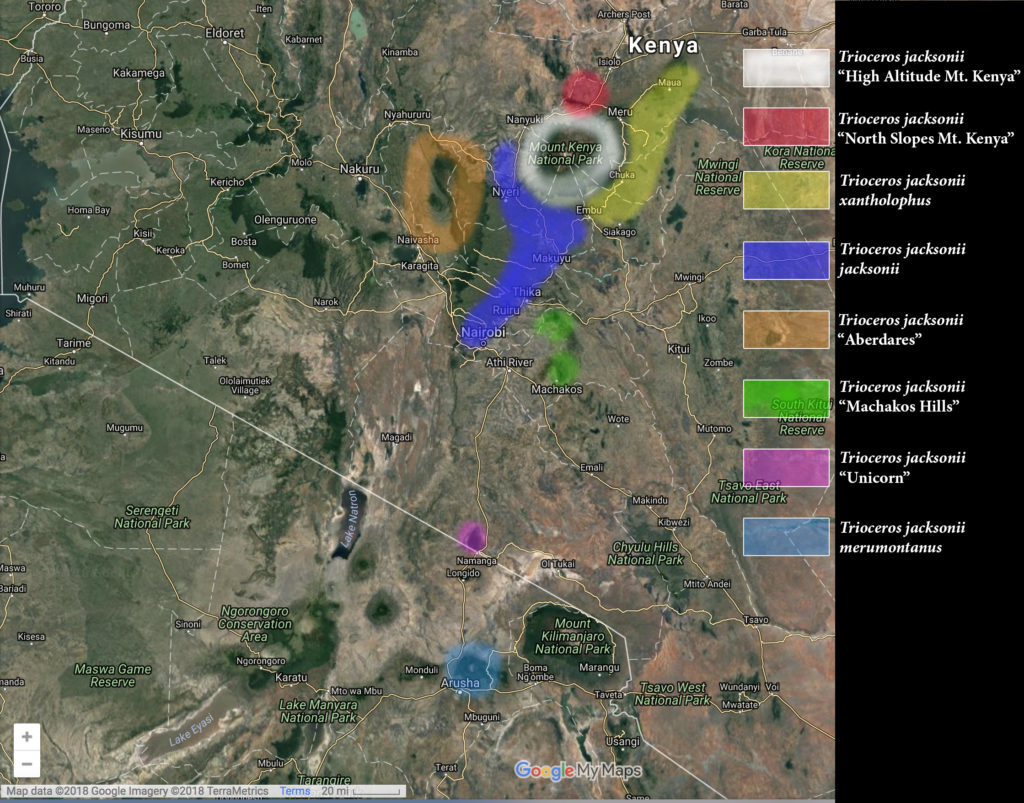

The other subspecies depicted on the range map are presently considered lumped under the Trioceros jacksonii jacksonii subspecies. All subspecies are from Kenya except the T. j. merumontanus which comes from Mt. Meru across the border in Tanzania.

Trioceros jacksonii xantholophus, the Yellow-crested Jackson’s Chameleon, is the largest of the three subspecies. This is the most commonly seen subspecies in the pet trade. Originally from Kenya, most individuals in the US pet trade are from the feral population on Hawaii or a transplanted population on the US mainland.

Trioceros jacksonii jacksonii. This subspecies has become a catch-all for all the undescribed subspecies of T. jacksonii. The variation is immense. The most commonly seen member of this subspecies in the pet trade is from the population on the Machakos Hills in Kenya. The male is brightly colored and is the one pictured here. This locale is accurately known by the name Machakos Hills Jackson’s Chameleon.

Trioceros jacksonii merumontanus. Also known as the Mt. Meru Jackson’s Chameleon, this is a smaller member of the Jackson’s Chameleon species. It is brightly colored and found on Mt. Meru in Tanzania.

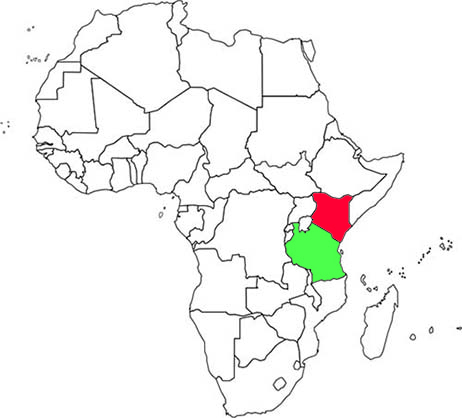

Jackson’s Chameleons originally come from Kenya and Tanzania. Though the largest subspecies, T. j. xantholophus, or the Yellow-crested Jackson’s Chameleon, has populated on Hawaii.

Species Reference Sheets

Click here for a .pdf guide to the many variations found in the Jackson’s Chameleons over its wide range. These variations are either undescribed subspecies or could even be elevated to species level. This will all be determined by scientists studying the taxonomy in the coming years. The most important thing for herpetoculturists is to recognize the wide range and, thus, account for differences in husbandry.

Common Types of Jackson's Chameleons

Trioceros jacksonii xantholophus (Yellow-crested Jackson's Chameleon)

The largest of the three Jackson’s Chameleon subspecies, T. j. xantholophus (or, affectionately, just “Xanth”s) is the most common. This chameleon is from the area around Mt. Kenya in Kenya, Africa, but has found its way to Hawaii in 1972. There are also reports of populations in other states of the USA such as Florida, Louisiana, and California, but verification of these populations is difficult.

This was the main chameleon (sub)species export in the 1970s. After Kenya stopped exporting this chameleon they started coming in from Hawaii where they had become a feral species. Although moving the chameleons off the island is illegal (except for small numbers of personal pets) there seems to be no scarcity of them in the US trade. Unless specifically designated, a T. j. xantholophus in the US is probably of Hawaiian origin while in Europe they are almost certainly of Kenyan origin. The males have highly developed three horns while the females almost always have only small nubs. Colors of both sexes are a bright and pleasing flow between lemon and lime colors.

A male T. jacksonii xantholophus from Kenyan bloodlines

A female T. jacksonii xantholophus from Kenyan bloodlines

A first generation (F1) captive born T. jacksonii xantholophus from Kenyan bloodlines

Trioceros jacksonii jacksonii (Machakos Hills Jackson's Chameleon)

The T. jacksonii jacksonii subspecies is a very diverse set of chameleons and certainly includes many subspecies and possibly species. Thus, a chameleon accurately labelled as T. j. jacksonii could be any number of chameleons. The most commonly encounter individual in the pet trade is the form from around the Machakos Hills. The males are brightly colored and the females can sport one or three horns. You will see many different common names such as “True Kenyan Jackson’s Chameleon”, “Rainbow Jackson’s Chameleon”, “Trioceros jacksonii willigensis”, and anything else importers can dream up. The “willigensis” name was given unofficially and is not recognized by the scientific community. Hobbyists often call them “jax jax”.

The Machakos Hills Jackson’s Chameleon is slightly smaller than a full grown T. j. xantholophus. Other members of the T. j. jacksonii can be much smaller. There is a great diversity in this subspecies so we must be careful to know what locale ours is from. As this information is often difficult to obtain you must be aware that the chameleon you have may or may not thrive under the conditions suggested for other Jackson’s Chameleons.

This subspecies causes confusion in the community as females can have one nose horn or three horns like the male.

A male T. jacksonii jacksonii from the Machakos Hills in Kenya. There are a wide range of color appearances with in this subspecies. The Machakos Hills form is the most colorful.

A female T. jacksonii jacksonii from the Machakos Hills in Kenya. Note the three horns which cause confusion for those not familiar with this subspecies.

A first generation (F1) captive born T. jacksonii jacksonii Machakos Hills Jackson’s Chameleon on its first day.

A male T. jacksonii jacksonii from the Machakos Hills in Kenya.

A female T. jacksonii jacksonii from the Machakos Hills in Kenya.

Trioceros jacksonii merumontanus (Mt. Meru Jackson's Chameleon)

These are the miniature Jackson’s. We affectionately call them “Meru”s. The males have very long and impressive horns for their size. The females have one horn. These are a colorful subspecies with blues and yellows. They are a higher altitude species than the others and would benefit from a deeper dip in temperatures at night.

T. j merumontanus is the Jackson’s Chameleon that lives in Tanzania on Mt. Meru by the border of Kenya.

A male T. jacksonii merumontanus from Mt. Meru in Tanzania.

A female T. jacksonii merumontanus from Mt. Meru in Tanzania.

A newborn T. jacksonii merumontanus from the breeding group cared for by Jurgen Van Overbeke

Environmental Information

Most species or subspecies of Jackson’s Chameleon come from around Mt. Kenya. The mountain is so big that multiple populations have developed. The subspecies we are most familiar with, T. j. xanthlophus can be found along the band of Mt. Kenya from Chogoria to Embu. But go higher in elevation and you run into smaller three horned chameleons. Go around Mt Kenya and you will find even more different forms. This is why defining subspecies, or at least locales, is important. In the case of the forms most commonly represented in the pet trade, T.j. xantholophus and the Machakos Hills form of T. j. jacksonii are from the basic same elevation and their care can be identical. The Mt. Meru variety, T. j. merumontaus, though is from much higher elevation and higher UVB levels and lower nighttime drops can be expected to be needed. Though we have yet to give a numerical value to what these needs would be.

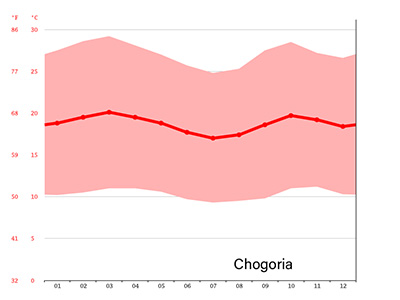

The Jackson’s Chameleon is found close to the equator and so their seasons are wet and dry instead of hot and cold. They encounter two wet seasons and two dry seasons. Although they are close to the equator they are at a high elevation and so have developed to function within the cooler temperatures of the mountains and expect a distinct nighttime drop. The two charts below show annual temperatures from Chogoria, a city nearby the T.j. xantholophus range and a precipitation chart. From here ou can see that

This annual temperature graph shows that the general area where the Yellow-crested Jackson’s chameleon is found rarely get into the high 80s and spends much of the time in the mid 70s. We have easily seen in captivity that these temperature ranges are important as Jackson’s will seek shelter when temperatures spike above the mid 80s and soon will start to show signs of heat stress.

What may surprise many people is the nighttime lows down into the 50s all year. And, in captivity, we see Jackson’s Chameleons that are not able to get this deep rest at night slowly decline in health.

Jackson’s Chameleons experience two rainy and two wet seasons. From March-May and Oct-December there is ample rain. In between there is relatively little. Jackson’s Chameleons have shown to be resiliant little tree dragons and have been able to adapt, to varying levels of success, to the environmental conditions of Hawaii, Southwest US, and South East US. This does not mean the conditions are ideal even if there are sustained populations. Thus we always go back to the original range and try to replicate those conditions.

There has been no serious experiment yet of the effect of receating two rainy seasons in captivity. A test like his may provide us with a learning opportunity with regard to mating success and timing of giving birth.

Multi-Media References on Jackson's Chameleon Natural History

Jan Stipala in Kenya

You can hear Jan Stipala discuss his journey through Kenya where he searched for the different chameleon species including the Jackson’s Chameleon.

Bill Strand

Mountain Dragons with Jan Stipala

Jan Stipala returned to the podcast and talked to us about planning our own trip to Kenya. On this episode we talked about the ranges where the Jackson’s Chameleon could be found.

Bill Strand

Ep 147: Planning a Trip to Kenya with Jan Stipala

This is the habitat of Trioceros jacksonii xantholophus in Kenya. Image by Jan Stipala

A view of the Machakos Hills, Kenya in which the Machakos Hills Jackson’s Chameleon resides. Image by Jan Stipala

Petr Necas in Kenya

Habitat that Petr Necas found T. j. xantholophus. Notice the disturbed landscape for farming which the Jackson’s Chameleon has adapted nicely.

Petr Necas has travelled the world to study chameleons in their natural habitat. His observations have provided valuable insight into the natural conditions we seek to replicate in captivity. He offers his insight into the captive husbandry of Trioceros jacksonii xantholophus from direct observation of these chameleons in their natural Kenya.

“Trioceros jacksonii xantholophus typically inhabits altitudes around 1500-1700m a.s.l. In a belt across the eastern foothills and slopes of Mt Kenya (from Embu to Meru) and extends more northeast to Nyambene range as far as Maua and beyond.

The climate is relatively stable throughout the year if it comes to:

temperatures (daily minimum around 10’C/50’F, daily maximum 25-28’C/77-82’F)

and air humidity (daytime under 40% – as low as 20%, night time always 100% with frequent fog)

There are two rainy seasons there (March to May and October to December) with rich precipitations and dry season, when rains can be scarce to absent for several months.

They spend their day, with the exception of early morning and late afternoon hours, in dense bushes, where the temperatures (on sunny days) can be 5-8 degrees lower than the given maximum.

In the captivity,

It is absolutely necessary to copy the main tendency of the climate:

1. High humidity at night time

2. Low humidity at daytime

3. Temperatures at daytime only 20-23’C (68-73’F) with possibility to bask twice a day for max one hour at 28-32’C (82-90’F)

4. Temperatures at nighttime under 15’C(60’F)

These conditions are essential for their wellness

The most frequent mistakes in husbandry are:

Low humidity at nighttime (leading to dehydration and necessity to heavily drink, which they normally do not do)

High temperatures at night (leading to lack of sleep, exhaustion)

High temperatures at daytime combined with high humidity (leading to URI, TGI, mouthrot, eye infections)

Providing them the right conditions leads to strong and vivid animals that can last in the captivity for up to 8 years and reproduce many times…”

Listen to me interview Petr Necas on his observations of Trioceros jacksonii in Kenya

Bill Strand

Ep 83: Kenyan Xantholophus Jackson’s Chameleons with Petr Necas

Mary Lovein in Hawaii

Though no longer in print, Mary’s book Chameleons in the Garden has been a very popular reference amongst chameleon enthusiasts.

Mary Lovein is an artist that lives in Hawaii. One day she was surprised to find a miniature dinosaur in her backyard and that started a life long fascination with the Jackson’s Chameleons of Hawaii. This led her to publish the book “Chameleons in the Garden“. It is, sadly, out of print, but is still available from time to time on used book sites and well worth picking up. Mary was able to observe the comings and goings of various Jackson’s and was able to get to know them so well that they were named and could easily be identified.

She shared her observations in the Chameleon Breeder Podcast episode Ep 33: Jackson’s Chameleons in Hawaii.

Bill Strand

Jackson's Chameleons in Hawaii with Mary Lovein

Conclusion

The key to discovering the optimal husbandry for any chameleon is to understand the conditions they developed under. The Jackson’s Chameleon is a unique chameleon in that there are a number of feral populations that have grown in Hawaii and on the US mainland from California to the Southeast. It is curious that, of the major chameleons in the pet trade, that the one with the most exacting requirements would be the one most represented in the most feral populations. This is itself presents us with a mystery. Why are they sensitive in captivity, but seem to have a wider tolerance in nature. And it is by the process of answering this question that we fine tune our captive husbandry even further.

Navigation

This seminar is part of the Jackson’s Chameleon Profile.