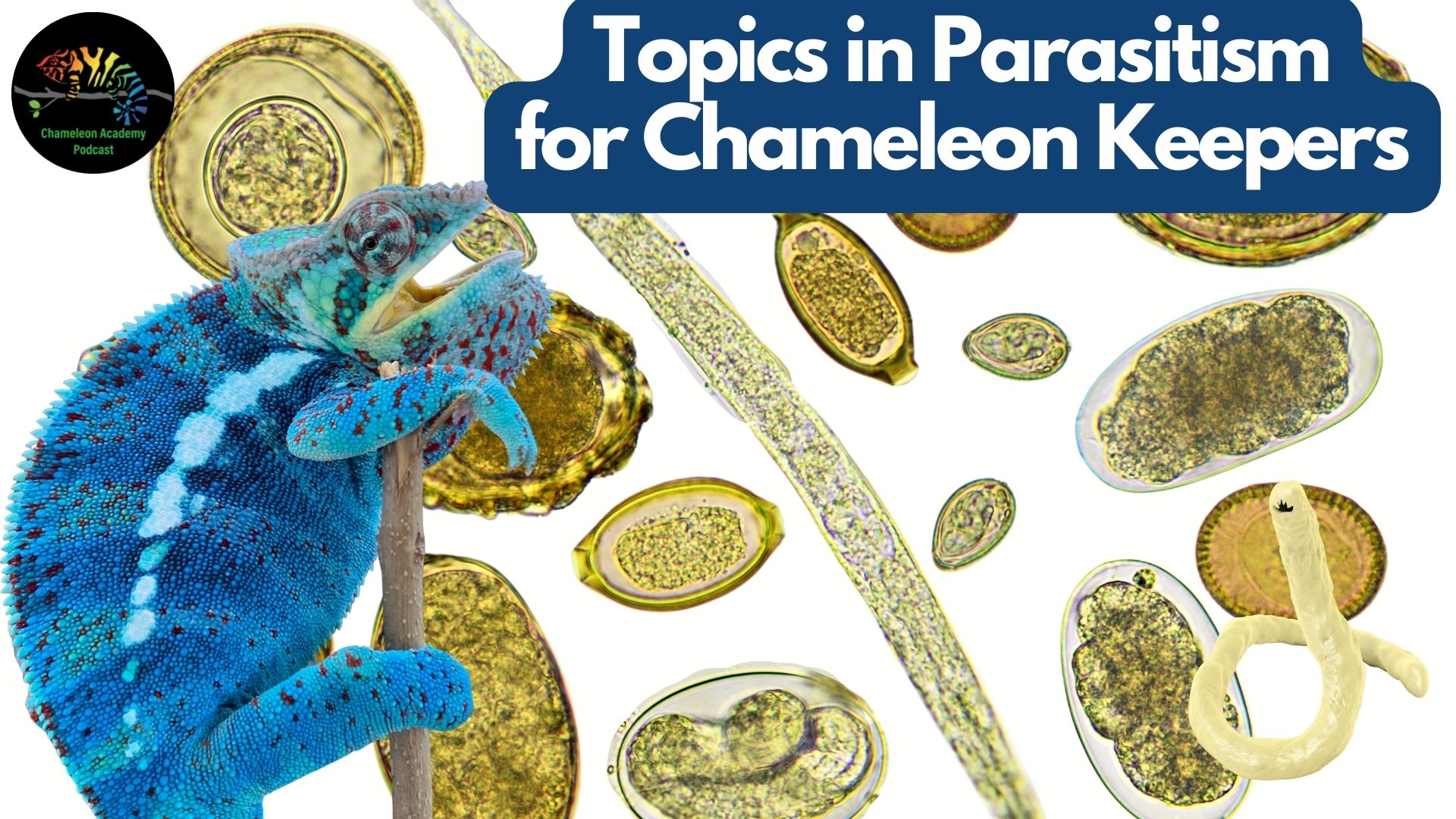

S7 Ep35: Topics in Parasitism for Chameleon Keepers

Every living animal has parasites. Even parasites can have parasites living on them. Today, I am going to present topics related to parasitism and then get us thinking about what next steps we can take as a community.

Embedded Podcast Player

Learn how to do your own Parasite Check!

Hunting Microscopic Chameleon Parasites is an asynchronous course you take at your own pace while supported by the instructor, fellow students, and the alumni. This is a community powered course so you are doing it on your own time at your own pace, but you are not doing it alone!

Click here to learn more

Transcript (more or less)

Introduction to Parasitism

The field of parasitism is vast and worthy of multiple lifetimes of study. And, I have to tell you, once you dig into it and start learning about the lifecycles it is addicting. You may think it is disgusting to think about worm living inside you stealing your nutrients, but there is an amazing, and I don’t use that word lightly, and amazing world under that microscope. We know a lot about it, but there is so much we are still learning.

I have done parasite introductions before. The challenge with a topic like this is that it is so complex that trying to give a good introduction in 30-45 minutes will just leave people confused. So what I am going to do is concentrate on explaining concepts and topics that you won’t necessarily find often discussed. I am going to share with you the wonder of parasites. Yes, you’ll learn something along the way, but if you come away from this episode excited for my next episode about parasites then I will have accomplished my mission! And, there will be a number of episodes on parasites after this. Today is less a tutorial lecture as a discussion around the digital campfire as to things for us to think about.

There are an overwhelming different types of parasites external and internal. I admit to having a certain affinity for learning about the lifecycles of the internal parasites known as helminths which are the parasitic worms. I enjoy the nematodes to be more specific, and, if pressed, I would have to confess to having a bizarre fascination with the hookworms in particular. So, you might find I talk about my favorite worm a little more than most. But hookworms are an excellent group of creepy crawlies to use an an example!

Our wonderful internal parasite have evolved to have curious lifecycles. Indirect lifecycles are out of a science fiction movie with all the stops and form changes they go through. But we in the Chameleon world focus more on the direct lifecycle parasites because that is what can get out of control in our captive conditions.

So, let’s take the nematodes, which are round worms, with direct lifecycles. They get to the various places in our body that they are going to call home, grow up, and spend their life eating and producing thousands of eggs a day that go through the digestive system and are pooped out. Those eggs soon hatch and then go through the most incredible journeys to get their infectious stage back into the mouth, or skin, of the appropriate species. And, no, any species won’t do! Yes, there are some worms that can infect multiple species and some that are able to jump genus and, at least, live within the wrong host. But most are highly specialized to a particular species. And this is because of the nature of how they know where they are. They are highly dependent on body chemistry to know where to go in the enormously huge dark and noisy world that is the human body. Just a little something off and they will get lost. For example, Hookworms latch on to your bare feet, find a hair follicle, excrete some enzymes that allows them to break though the skin there and then look to get into the blood stream to take a tour of the body that includes the heart, lungs and trachea to eventually make it to the small intestine. They do this with disturbing precision. Unless we are the wrong host. When we walk along the beach that allows dogs, we may come home with itchy red squiggly lines all over our feet. It is sometimes called ground itch or creeping eruption. Or, when you go to the doctor, cutaneous larva migrans. This is the dog hookworm getting lost because we aren’t the right host. It is confused and can’t figure out how to get into the bloodstream! So it wanders all around your foot. This is an example of what happens when a parasite is introduced to the wrong host. We are the definitive host for the human hookworm. We are a deadend host for a parasite that can survive in our body, but it cannot reproduce. Now, I hate to tell you that we are not 100% the deadend host for the dog hookworm. While it gets lost when it tries to invade us through the skin route, there are cases recorded of infections resulting for oral ingestion of the infectious dog hookworm larvae.

Now, wait a minute! As fascinating as this is, we are here to talk about chameleon parasites. Why are we talking about humans and dogs? Well, the facts of life are that there is precious little research on the lifecycles of reptile parasites. Most of the research revolves around identifying species and how to kill them. There isn’t much beyond that. And, why would there? Establishing the lifecycle of a microscopic parasite that changes form between life stages and is maddeningly difficult to raise in the lab because of this is very expensive and may not produce important data. Sure there is value in scientific curiosity, but unless you expect to find something that will be more effective and/or cheaper than Panacur for removing a hookworm infection it may be hard to justify research dollars. And so, this is why we need to study the work done with human parasites. There is a wealth of knowledge and a couple hundred years of experiments to reference. Though it is true that the reptile versions of the human parasites may not have the exact lifecycle, the research on the human form gives us a very good start for what to watch out for.

I brought up the hookworm to explain the difference between a definitive host and a deadend host. The other important term is a reservoir host. This is a host that the parasite spends some time with in order to be passed on to their definitive host. They don’t cause any disease in the reservoir host and do nothing except wait for the definitive host to come along. Well, okay, I need to take that back. There are some cases where they do get involved. And here is where you may want to sit down for this. It is not uncommon for parasites wanting to find their definitive host to modify the behavior of their reservoir host in order to get them all the way. There are some flukes that hitch a ride in a fish but they eventually need to get into a bird for their next lifestage. They literally change the fishes behavior to make it swim on its side and flash into sunlight. This becomes a beacon for every bird around and attracts them to the fish. So the parasite makes the fish behave in a way that will get it eaten. Pretty devious I would say. But that is hardly the only case! One parasitic hairworm that uses grasshoppers as an intermediary host drives their grasshopper host to commit suicide by throwing themselves into a body of water so the parasite can go on to its next stage. Toxoplasma gondii is a protozoan parasite that needs to get itself to its definitive host, the cat. And they need to take a ride in a rat to get there. So Toxoplasma changes the rats brain so, not only does it no longer fear the smell of cat urine, it is actually attracted to cat urine. The danger sense in the brain is reduced and the rats become more reckless. Of course, they get eaten by the cats they no longer fear. So, how do you like the idea of a parasite changing your personality for its ends?

So, the cat is the definitive host. The rat is the intermediary host.

And we humans are a deadend host. Wait, what? Yes, it is estimated that one third of the human population is infected with toxoplasma gondii. We are often considered a deadend host for toxoplasma gondii because toxoplasma would go extinct if it relied on us getting eaten by a cat. What are the chances of us getting eaten by a cat and spreading Toxoplasma to its definitive host? Well, enjoy your status as a deadend host, But I think there was a time not too terribly long ago that we were a reservoir host. If we ever went back to the caves with smilodons, the saber tooth cats, roaming around we would get to be back to an active member of the Toxoplasma lifecycle. You never knew you had it in you, did you? Congratulations!

So, some of you are a bit distracted by the suddenly urgent question, what does toxoplasma do to us? The answer is that it does the same type of thing to us that it does the rat. We become aggressive, impulsive, and less careful. So, for those of you who believe your personality to be your own, there is a 33% chance you are sharing ownership of your personality with a protozoan parasite.

Knowing which parasites have a direct lifecycle, meaning they can reinfect your chameleon, or indirect lifecycle, meaning they can’t reinfect your chameleon without a snail or other lizard or whatever gives you an idea of how serious you need to take the infection. Do you need to tear down, steam, bleach and sun clean your enclosure or do you just need to practice basic cleanliness? There is a huge difference in urgency and reaction between having a coccidia infection and a tapeworm infection. A good reptile vet will be able to do a fecal exam, determine what parasites are present, figure out treatment, and let you know the urgency depending on what type of parasite and the level of infection.

What transfers over?

Figuring out the lifecycle of a microscopic parasite is very difficult. It takes teams of scientists, serious funding, human misery, and dumb luck to figure it out. I mean you have these indirect lifecycles that go from poop to snail to fish and turning into different forms. Do you know how we figured out that hookworms get in through our skin? A scientist in 1886 accidentally spilled a vial of water with infectious stage hookworm larvae in it on his hand. Then he had the curiosity to wonder if the irritation he felt would result in an infection and, sure enough, six weeks later he was producing hookworm eggs. So, this happy little accident solved a riddle.

Now, you may think this could be an obvious conclusion, but worms gaining access to our bodies through the skin is very rare. The skin is an amazing defense and any nematode would have to have an impressive entry method to break through. And, yes, it does. The larvae specifically looks for a hair follicle, crawls down it, and then is able to dissolve the skin at the base to get into the bloodstream to begin its tour of the body looking for the lungs to hop off their raging rapids ride.

More than just a very cool and morbid factoid, this brings up some serious questions for us herpetoculturists. How much of the human hookworm lifecycle translates out to the reptile, or specifically, chameleon hookworm lifecycle?

Because we in the reptile community do not have the funding that researchers of human ailments get, we will not be able to start at ground zero and build up the lifecycle. It is worthwhile for us to take the human version lifecycle and see what applies. This isn’t just what we parasite nerds think is fun. Consider this.

The human hookworm lifecycle is that the eggs are sent out of the human host in the feces. The eggs hatch in the poop and the first two worm stages feeds on the microbes. But after the second molt the worm becomes infectious and searches for the highest point in the environment and they wait for humans to walk by and brush their blade of grass or rock whatever they are hanging out on. If the conditions are right they can do this for six weeks before dying. And this tiny nematode can travel four feet looking for a new host. You ever wonder why outhouses are six feet deep? It is, literally, so the hookworm larvae, which ravaged the civil war era Southern US couldn’t crawl out. How tall are our standard chameleon cages? Now, you could say that our reptile hookworm is much smaller than the human hookworm so the distance for mobility, if the reptile hookworm does, indeed, travel, should be proportionally shorter. Which would be a valid hypothesis worthy of testing. But we also need to consider that we have no idea what is magic about four feet. The hookworm larvae don’t run out of energy. They can spend weeks traveling up and down stalks of grass looking for a new host. So that isn’t the reason they stop at four feet. So, until we know why human hookworms stop at four feet we won’t know if size has anything to do with what the reptile hookworm may do. So, yes, consider this a rallying call for any of you out there who are interested in biology and are wondering what to study!

You see how this might turn our concept of quarantine into a bizarre alley. If reptile hookworm larvae have this ability to get in through the skin, would they also have the ability to be mobile and search out their host? Anyone here see the implications of this line of questioning?

The need for sanitation in our cages just took a bizarre turn. Many of us know to be careful that feeder insects do not come in contact with the poop of a wild caught chameleon in quarantine. But how many of us have considered that worms could hatch and then actively search out the host without the need to go though the mouth?

Now, remember, I know of no study that has looked at whether hookworm larvae are mobile and will track down our chameleon or other reptile. My point here is that the fact that human hookworms do this is compelling evidence that it is something we should consider as possible. This is how we leverage the well funded human parasite research. We can gather clues as to where to look.

There is a reference to Kalicephalus, the snake hookworm, being able to go in through the skin. So, what does Oswaldocruzi, the lizard hookworm do? Can that go though the skin? Does that have the ability to be mobile? See, these are the questions we need to consider and we have precious little data to work from.

But a warning. Be careful when doing research. Especially where we have only scattered references (like in the niche of a niche of a niche that is the topic of chameleon hookworm lifecycle), it is easy to fill in the blanks, make assumptions, and go off in the wrong direction. For example,It is very easy for one researcher to say there is no account of this hookworm to be infectious by ingestion and the next researcher to simply state that this hookworm cannot be infectious by ingestion. Do you see the subtle difference between the two that has huge implications in message? A researcher saying that there is no study or evidence presently known does not mean it doesn’t happen. It means that no one has specifically looked to figure it out. It is not saying it doesn’t happen it is saying we haven’t explored that yet.

Example, There are two hookworms that are responsible for the majority of human infections – Ancylostema duodenale and Necator americanus. Both are able to infect by burrowing in through the skin, but only the Ancylostema has record of also being infectious if the larvae are swallowed. Well, unless the larvae of Necator go through some development that requires the blood environment, it should be able to by pass the whirlwind trip through the body and take the short cut to the digestive system as well. But I can find no paper saying this has been discovered not to happen. Just a number of unsupported statements saying it can’t. So, just a warning, be very careful what you take and run with. I actually, still don’t have an answer on this one so I have to keep searching until I discover whatever paper says infection from ingestion can’t happen. It just seems like it would be a given that it could and that scientists would require proof that it couldn’t. Either that, or there would be a well known transformation that happens in the blood.

On the other hand, there is a gray market in selling hookworms to people who believe that the human body actually needs parasites. They offer Necator Americanus and send you a patch to put on your skin rather than a vial of liquid. So, I suppose that would suggest someone has tried and decided Necator was through the skin only. But I am grasping at straws here.

By the way, Helminth therapy runs under the hypothesis that the human body evolved throughout history to expect that there would always be hookworms and other worms that needed to be dispatched. So the body is on the look out for them and assume they exist. The idea is that this is the origin of Crohn’s disease where the body is attacking itself because the parasites it is suppose to attack are not there. By giving the body parasites to attack the idea is that things will be back in balance. Now, I don’t see mainstream medicine supporting this approach. If you go onto Helminth therapy websites, hookworms are called symbiotes and are painted in a much more positive light than you are used to. Of course, there is the obligatory section on how to pay in bitcoin because it doesn’t look like traditional credit cards are taken to pay for the $450 regimen of three doses.

But, let’s get back to our quandary about how active reptile hookworms are in seeking their host. It could very well be that I am sounding a needless alarm. For example, pinworms are very different between humans and reptiles. You are not going to find pinworm eggs in human feces because the – and a warning here for the faint at heart, this gets disgusting – female crawls outside the anus and lays her eggs on the skin. She produces a substances that causes the skin to be itchy so the human scratches their bottom, picks up the eggs, and, eventually, sticks their fingers in their mouth to continue the bizarre lifecycle. This is common in children. But chameleons can’t scratch their bum with something that has a chance to be put in their mouth. So, the lifecycle is different. You do see pinworm eggs in chameleon poop. So, it is not given at all that the reptile versions of human parasites retain the exact same lifecycle. But what the extensive human parasite research gives us, at least, is an idea of what to look for.

If anyone has a chameleon that is positive for hookworm eggs and has a microscope, perhaps put that poop in a moist warm environment and see if you can detect worms anywhere else in the cage in the coming weeks. It is something I would like to try and I have been looking for hookworm positive poop. But, I guess I have been lucky that, in the last year, no wild-caughts have come back with hookworms. It is strange what I am disappointed with.

So, how about we wipe the slate clean a little and do some thinking. How do parasites get back to reinfect a chameleon? You have a lizard that is in the treetops. Let’s take a canopy species like Trioceros owenii, or Trioceros melleri. They poop and the eggs in that poop go down to the forest floor. How in the world is a microscopic egg or larvae going to get back up to get in the chameleon’s mouth. Yes, we are concerned about feeders walking through the poop and picking up hitchhikers. But, in the wild, what standard food insect is hanging out at the forest floor and also being eaten? Bee are doing it. Would that mean that flies are the primary vector? It is a reasonable answer. And perhaps that is the best we will get. But it is not satisfying. In the world of human parasitic infection, even with direct lifecycles, we have uncovered elaborate strategies that even include behavior modification of the host. So it would figure that there should be just as elaborate strategies employed by chameleon nematodes to get their larvae 20 feet in the air and in contact with or eaten by a chameleon. If any of you wanted to go into biology, here is a lifelong field for you.

Cross species infection

Our next question is how well a chameleon parasite can infect other reptiles or, more of a concern, is how well can parasites from other reptiles infect chameleons? And this comes to to forefront when we start talking about feeding our chameleons wild insects from the US or Europe. How many alligator lizard parasites would find a suitable home in a chameleon body? Now, on the surface you might think they are both lizards. It should be no problem. But it is far from certain. In fact, it would be surprising if parasites from the common reptilian ancestor millions of years ago maintained the ability to infect both the alligator lizard and the chameleon who have evolved on opposite sides of the Earth. Because the parasites are evolving with their hosts. And the parasites are dependent on the chemical cues within the body to tell them where to go. Slight changes in those chemical cues and your hookworm larvae will never know they have reached the lungs and it is time to get off the blood stream bus. So, the question is how much does the inside of the body stay the same? And the answer is that we don’t know. But this at least is an easy test. Exposing a parasite free chameleon to alligator lizard poop that has been confirmed to have hookworm eggs would give us our answer. Obviously it would be more official if we identified the hookworm species and did this over a number of individuals. This would actually be a good scientific study with value beyond our community questions. I have seen mentions that Kalicephalis, the snake hookworm is not picky which hosts they infect, while others saying that coccidia tends to be species specific. I have gone beyond just accepting what I read in summaries and have taken to tracking down the study from which these statements come from, but that has become a laborious task which I have only just begun so I will plan on a future episode where I share with you the journey through all these papers and extract what is important for our uses.

But let’s dig into the situation we have about the decision regarding keeping our chameleons outside or feeding wild insects. Even if the reptile and parasites have evolved separately for millions of years, what are the chances and effects of them being a dead end host and seeing some sort of health effects, but no positive on the fecal? And we don’t know much about this. So, in an absence of information, we need to allow the keepers who, out of abundance of caution, refuse to feed wild caught insects and, the keepers who feeder wild caught insects every chance they get, to co-exist and look for solid answers together.

And this bears repeating. There are so many things we do not know about chameleon husbandry, but we still have a decision to make. We take all the evidence, weigh the risks and benefits, and go in a certain direction. We gather information and then adjust our direction based on any new information coming along.

I, personally, feed wild caught insects every chance I get. I am excited for the diversity of nutrition that brings. I haven’t seen a bloom of parasites in my chameleons over these many decades and so I have no indication that this is harming my chameleons. But maybe I have just been lucky. And even if my arid environment doesn’t harbor parasites that can leap to chameleons that doesn’t mean it is safe in Florida. Do you see how me transforming my individual observations into a blanket statement could turn some valuable data points into an incorrect, overreaching, and dangerous black and white sound bite to be repeated ad infinitum on social media? I know we all have to memorize the sound bites when we start out with chameleons because there is just so much to absorb that you’d go crazy trying to understand it all deeply. But for those that have the basics under your belt, your chameleon is doing fine, and you have some time to dig deeper into all this husbandry items, allow yourself the gift of not knowing. Because that brings you closer to the truth. It is okay for you to make a decision based on the data you have and, at the same time, accept that other people will have different conclusions. As more information becomes available, as it always does in the march of science, you can adjust your decisions. And this doesn’t mean someone is right and the other one is wrong. People who guess the right answer are not geniuses that see the great beyond. You made a guess that could have gone either way. If you guessed right then good for you, but that doesn’t represent any superior insight. So, don’t go off on social media as if you are some great seer. The next time it will be the other keeper and their guess and you all go back and froth holding up bragging points on things that are undeserved. How about we respect the people who decide that the possibility that there can be parasites that jump to chameleons from alligator lizards or whatever you have natively is worth tightly controlling the diet and we allow the people like me who want the benefit of diurnal feeder diversity to continue on with the full expectation that we all will be adjusting what we do when more information goes available. And, also, expect that the real answer won’t be black and white. Because there is some, at least anecdotal experiences of parasites jumping between species here in the US. So the final answer won’t be that it can’t. It will be a better grasp on the risk.

Let’s not double down on our guesses so much that we are fighting each other on which guess is best. Let’s decide our approach and keep our eyes open for data that adds to our collective knowledge and share freely. None of this accepting only data that supports our guess so we can win the Facebook argument. Bring it all to the table and we will all learn. Whether or not you feed wild insects for fear of parasites (or pesticide residue) is a prime example of how we, as a community, can kill our progress forward. When we break into our warring tribes over issues we only have a basic grasp of we kill discovery because we are all working to prove our point and be right.

At the Chameleon Academy we embrace not knowing and our pride is not in having an answer, but in knowing what we do know and being comfortable acknowledging what we don’t yet know. And that is why, when new information comes available, and is deemed credible, that I will change what the Chameleon Academy presents as the latest in chameleon husbandry. So, the message is, the real power lies in being comfortable with not knowing, but not being content. There is a lot of work to do.

Non-infectious positives

We also need to be careful when it comes to our tests. And here is where the almost overwhelming task of species ID comes in. How do we tell the difference between infectious and noninfectious parasite eggs? Are these eggs we are seeing actually part of an active infection or were they consumed and not infectious. Presumably, if you see eggs in the feces then it would make sense that there is an infection. Because how else would eggs be produced if the parasites are not reproducing? But if the feeder insect brings along some of these life stages that are not infectious to the reptile, but look like the infectious species then we can make false identification of an infection. Of course, egg density is certainly a sign. Finding a couple eggs here and there invites more scrutiny than a heavy density of eggs on the microscope slide. Parasites can produce thousands of eggs a day and so there are ways of checking what you are seeing.

The common accusation that my chameleon got parasites from the cricket farm demands a bit more scrutiny. How would the infectious stage of a parasite that is compatible with your species be present at a cricket farm? Although this is not an impossible situation, there are many much more likely scenarios that can be built up. Though we all tend to stop our exploration once we arrive at a scenario that places the responsibility elsewhere. The problem with this is that you are destined to repeat whatever it is that happened if you ignore other possibilities.

I am not saying you cannot get parasites from feeder insects you purchase. I only advise caution and considering that possibility with as much critical thinking as any other option. Remember that microscopic parasites have to figure out how to get enough of them into hosts in the trees to continue the species. So they produce an enormous amount of eggs with the situation that most will die. But they are sticky and will travel along with your hand, your phone, the cage latches. If you pick up poop, close the cage, wash your hands and then come back to feed then when you open the cage back up, your newly scrubbed hands suddenly are spreading parasitic eggs, oocysts, or what not. So you are up against millions of years of evolution that has fine tuned the delivery mechanism for these parasites. I wouldn’t feel too bad about it. Just be aware of it and use that awareness to heighten your vigilance of what you touch.

Conclusion

The subject of endoparasites is beyond huge. It is worthy of a life time of study and research all its own. My purpose in this episode is to expose you to that incredible world and share the wonder that I have for it. There are so many more questions I hope you have. What are the difference between the parasite types? How do anti-parasitic medicines actually work? What kind of microscope do I need to do my own fecals? You can be sure we will be having many more conversations about this incredibly fascinating subject.

Thank you for joining me here! The side effect of being interested in chameleons is that you get exposed to a wide array of supportive topics and parasites are one of them!

This is Bill Strand signing off. Have a great week and I will see you next time!